A Fair Price for Cobalt?

Editor’s Note: FairPhone asked Christian Kuijstermans from ActionAid Netherlands to write about his recent investigation into Cobalt minerals in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Cobalt is one of many minerals in a mobile phone; mainly found in its batteries. Most of the world’s Cobalt originates in Africa, half of which from the mineral-rich province of Katanga in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Even though Cobalt is not one of the “conflict-minerals” singled out by the international community (the Cobalt production areas in Katanga are – at the moment – rebel, and therefore conflict-free), it does not mean that production is fair.

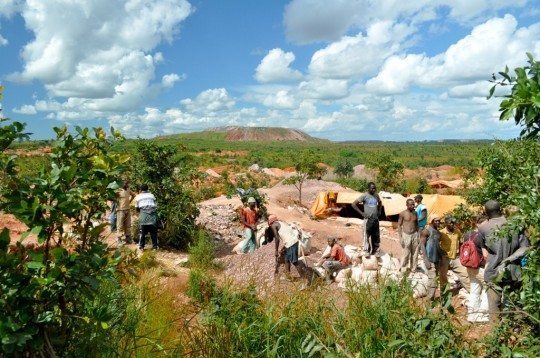

A large part of the mining is done by hand (artisanal mining) in mines 30 meters under ground. Estimations of the number of artisanal Cobalt miners in Katanga vary between 50,000 and 100,000. Taking into account the large families and other dependents, some 400,000 Congolese could easily be dependent on artisanal Cobalt mining, but most likely much more than that: enough reason to see whether FairPhone can contribute towards setting up a fair(er) Cobalt chain.

The Congolese Mining-law stipulates that to be able to work as an artisanal miner you need to be a member of a cooperative.

The idea of stimulating artisanal miners to group themselves is in principle a worthwhile idea. The reality of Congolese cooperatives, as I observed them in the Cobalt mining sector, is less laudable.

A cooperative can be registered on the basis of a single person and this has been the standard practice (of one or often a few influential individuals). These little (or big) operators, once registered, acquire rights for certain artisanal mining areas. Any artisanal miner in the particular mine has two options: either to become a member or to leave the mine. Apart from the miners themselves the middlemen (négociants) are also members of the same cooperative. As was explained to me, these middlemen invest in the mine worker(s). They pay for their upkeep in the first phase of preparing the pit (and during production), and also provide them with tools for mining. Allhough this also does not seem like a bad deal at first glance (where else would someone without access to money get hold of funds to start mining?), reality hits the mineworker rather hard again.

Fifty percent of all produce is being handed over to the middleman as compensation for the investment; the value of which greatly surpasses the investment made by the middleman.

The situation for the mineworker is further aggravated by the fact that in most cases a one-man cooperative controls the mining pit. The cooperative signs a deal with an investor (mostly a locally registered enterprise that serves as a go-between for the mine and the industry), who receives the exclusive right to buy all produce coming from the mine. The investor obviously handsomely rewards the cooperative (read: it’s owner, not the members) for this right. This means that the investor in effect controls the price paid for the Cobalt. A mineworker has no opportunity to negotiate price (there is only one buyer available to him); and has no option but to accept the price offered. The fact that he is a member of a defunct cooperative, and the fact that it is not occupied with improving the rights of its own members, is understandably of little assistance to him. Was that the end of the ordeal for the mineworker? No. The equipment used to measure the grade of the ore as well as the scales for weighing the raw ore are owned and controlled by the – exclusive – buyer.

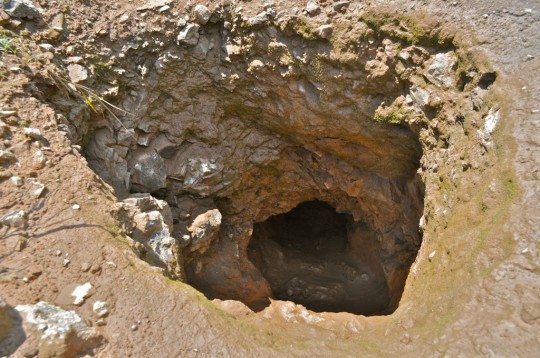

This mining tunnel has been deserted. The rain made it too dangerous to enter. The tunnel goes about 20 metres deep.

Tampering with both the grade as well as the scales is unfortunately a rather common practice. Questionable is also whether the price is established based on real world market prices, and whether calculations take the correct exchange rates between Congolese Franc and the Dollar into consideration. To top it off, a miner only gets paid according to the majority mineral, Cobalt, in the raw ore. He doesn’t get paid for any other minerals in the ore, of which there may be many (copper, silver, uranium, gold, etc). The above underlines why it would be worthwhile for ActionAid/FairPhone to focus on Cobalt production in Katanga. I have not even discussed addressing the difficult and dangerous working conditions for artisanal miners or the environmental damage caused. However, the above also shows that finding the right entry points is not easy. As several of my interlocutors explained during my visit,

a good start would be to have “real” cooperatives in the mines, those that represent and care for mine workers, thereby improving their bargaining position.

This is an environment where corruption is rife, legislation is flawed (more pro-industrial mining for instance), and its implementation is hardly enforced. Where political power has more to do with establishing access to government services and funds than it has to do with an obligation to serve the good of the people. And where as a consequence Darwin’s Survival of the Fittest theory sees new extreme aberrations, this is of course nothing more than a first step. Nevertheless an important one.

This is an environment where corruption is rife, legislation is flawed (more pro-industrial mining for instance), and its implementation is hardly enforced. Where political power has more to do with establishing access to government services and funds than it has to do with an obligation to serve the good of the people. And where as a consequence Darwin’s Survival of the Fittest theory sees new extreme aberrations, this is of course nothing more than a first step. Nevertheless an important one.

Christian Kuijstermans (1974, based in Cologne Germany) has experience working on human rights, governance and civil society in several African countries since many years, part of those on the ground in the Great Lakes Region. Since August 2012, he has been working as a part-time consultant for ActionAid Netherlands in its partnership with FairPhone.

Photos by Bas van Abel used by Creative Commons