The Fairphone 2 is reborn… as a circular microcomputer

November 27, 2024. It’s a date we will always remember. It’s the day our beloved Fairphone 2 came back to life… in the form of the world’s first circular microcomputer. We couldn’t be prouder of this wonderful project our partners at Citronics have been working on. And the timing of the launch couldn’t be better. With Black Friday right around the corner, it’s always good to see how we can use the growing mountain of electronic waste for something good. We sat down with Jean-Brieuc Feron, the founder of the Belgium-based low-tech consultancy, to learn more about this wonderful innovation that is literally resurrecting our old phones.

You used to work as a rocket scientist originally. How did you go from building rockets to recycling old smartphones?

As a child, my dream was to work in aerospace. That’s what led me to study engineering at university. But even then, I was interested in sustainability as a topic. As a student, I would volunteer to raise awareness about reducing waste on campus, or encouraging eating local produce and seasonal vegetables, that sort of thing. After I graduated, I started working in a Belgian aerospace company, developing a processor for a space rocket. That led to more similar projects, and before I knew it, ten years had passed by. I was living my childhood dream. But at the same time, I did feel something was missing. Aerospace was great, but I did feel we had problems to solve down here on Earth as well. Problems related to sustainability, climate change, energy technologies.

That’s when I found myself looking into green technology. Given my background in electric propulsion, greener transport was a logical fit. But as I poked around, I began to hear about low tech engineering. As an engineer, you are taught to design and assemble things, but you don’t really think about where all the raw materials are coming from, what the ethical and environmental impact of their retrieval is, what happens with these products after they reach the end of their life. I realized I was only adding to the problem. I decided I needed to quit the aerospace industry and start something of my own that was more in line with this low-tech design philosophy. That’s how Citronics was born. At Citronics, we take into account the environmental and social impact of what we want to make at the engineering and product design stage itself. We’re very similar to Fairphone in that way.

How long has it been since Citronics came to life? What are some of the other projects you have worked on?

So I quit my job at the beginning of the COVID crisis, around 2020. We first set up Swarn, which is a low-tech consultancy, working with major manufacturers to help them with solutions that would bring them more in line with a circular economy philosophy. One of the first projects we worked on was making wood pellet fuel out of green waste, such as old and used pallets from industrial floors. We don’t need to be cutting down more trees to make wood pellet fuel when we have so much used wood lying around. Another project I was very excited about was a new thermal battery design. Instead of electricity, it stores heat and could be used as a way to improve thermal energy production using phase change materials. We also collaborated with electric bike manufacturers, Cowboy, helping out with the power train design for their e-bikes. We then set up Citronics as a subsidiary of Swarn, as the retail brand that we will sell our own products under. Products like the circular microcomputer we’re working on with you.

Wooden pellet fuel, thermal batteries, e-bikes… and now circular microcomputers. Where did the idea come from?

Smartphones have always fascinated me in terms of their computing power. What was even more amazing was how we would use these super-powerful devices for just a few years and then throw them away, even when the components inside were often fully functional. The potential for reusing them for other applications was huge. That’s what got me thinking. The way I saw it, either people had thought about the business case here and thought it was a stupid idea. Or no one had actually looked into so far. So I thought, why not me then? So I started playing around, testing out my theories. Technically, I could reprogram the components, provide an internet connection using the 4G modem inside. 4G modems are an expensive component, if you have to buy them new. And there were so many functional modems just sitting in unused phones.

I started shopping my ideas around, and as it turns out, it wasn’t such a stupid idea after all. A few industry players started showing interest, asking for data sheets and potential costs. My idea suddenly became very real. I started thinking I wasn’t the only one crazy enough to think this might actually work. And that’s how we got rolling with the idea.

So when did Fairphone come into the picture?

It was actually through an old friend of mine. They had given me a Fairphone 2 to use, and I loved how easy it was to disassemble. The electronics part extraction is straightforward and is much more cost and time-effective, compared to working with a glued-up device. From the get-go, my ambition for this project was to make it at an industrial scale. I was going to need thousands of phones, if not millions, especially if I wanted to keep engineering costs down and amortize the debt involved. So I got in touch with Fairphone and you answered my call. I remember my first meeting with the team here. I got really technical and was afraid you wouldn’t understand my intentions. But you understood, and more importantly, you also realized the value of giving these discarded devices a new life.

Of course. At Fairphone, we hate electronic waste, and we’re always looking for ways to make sure we can reduce it as much as possible.

Exactly. It’s been a rewarding collaboration so far. The only regret is that there aren’t enough unused Fairphones out in the wild compared to other smartphones. Everyone’s still using their Fairphone. (laughs)

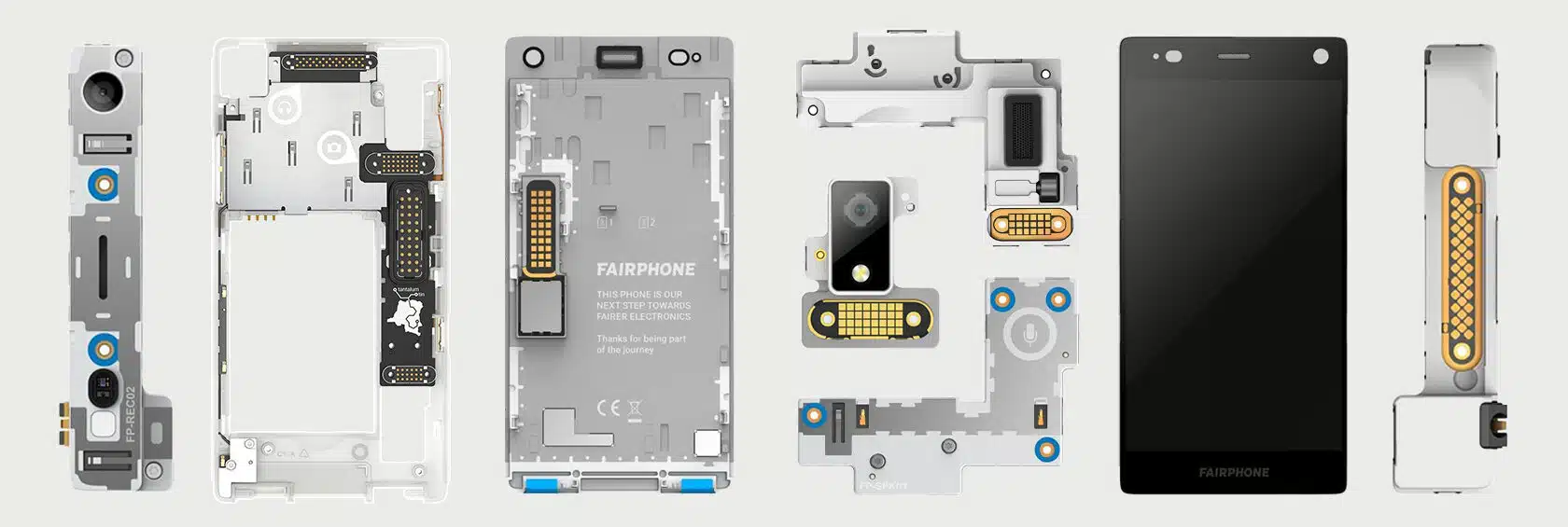

Devices can look broken, but that doesn’t mean everything inside is broken. Citronics live tests our old Fairphone 2s on their industrial floors, and extracts the working components. ©2024 – Citronics

Let’s talk about the star of the show: the circular microcomputer. What are its applications per se?

Microcomputers can be used for anything. It can sit in your pocket, like a smartphone, of course. But it can also be used on an industrial floor for the machinery there. It can control your heating system at home, send data and store it in the cloud, used on trains, e-bikes, ATMs, for education. The applications are endless.

The two key capabilities that are really important for a microcomputer is the processing capabilities and the connectivity capabilities. With the microcomputers we are making using Fairphone 2 components, you’re able to run a full-fledged operating system like Linux, and connect to the internet and other devices via 4G, Bluetooth, USB, ethernet and Wi-Fi, all the standard communication interfaces we have today. That’s really, really good, especially as an internet gateway device. It can gather data locally and send it back to a cloud server. This could be very useful for the industrial floor, or heating systems, or onboard computers on e-bikes. It can help optimize energy consumption, can be used for remote monitoring. That’s where it stands today. Down the road, we are also looking at integrating the displays and the touch-screen capabilities. This will open up even more possibilities and use cases.

Currently, with the Fairphone 2, the components would be quite standardized. But as you scale up and start using devices by other brands, how do you go about ensuring the specs are the same across?

With communication capabilities, this is not a problem. Like I said, 4G, Bluetooth, WiFi, these are the standard specs we have. In terms of processing power, we can group different devices with similar specs. So, while there will be minute differences between brands in terms of specs, they will broadly be the same. Depending on the processing power, we can create different families per se; low-performance, mid-performance, high performance, and so on.

Let’s talk process. Let’s say we send across a consignment of old Fairphones to your assembly room. What happens next?

The first thing we do is check if the device is live or not. Devices can look broken, but that doesn’t mean everything inside is broken. So on our industrial floors, we do a live test to see what’s working and what’s not. The motherboard extraction process is mainly a disassembly process. We sort all the components by materials (plastics, metal, and so on) or by re-use potential: we are already reusing the screws, and in the future, we will be reusing the screens definitely. There is a lot of potential with other Fairphone 2 modules as well, such as the cameras, the speakers and mics, and the USB ports. So we store them safely for now. Once the components are extracted and sorted, they are reprogrammed and tested. Once they are good to go, they are used in either our product assembly process, or shipped to B2B clients who need these parts. Everything is shipped out of the industrial floor.

This is really exciting stuff. With the circular microcomputer, we now have a feasible solution to make sure all our old devices keep getting a new lease of life in some form or the other! What’s next on the cards for Citronics?

We’re starting to work with some big industrial actors in the telecommunication sector on circular router projects. That’s very exciting. But we’re also looking at scaling up in a big way. We will start raising money early 2025 to fund our development.

Learn more about the Citronics circular microcomputer here.