On-site visit to cobalt mines in Congo, April 2017

Just a couple months ago in April, I went to the DRC together with team member Sylvain, to continue our quest for more responsibly mined materials. This time was all about cobalt, a critical material we need to produce our battery. For some part, we were joined by a documentary crew that is following us for several months to show our work as an alternative way of doing business. See a short excerpt of our time in Congo.

During the trip, we were able to see many steps of the cobalt supply chain and talk to different local and international parties. Thanks to the help of GIZ (German Development Cooperation) and BGR (Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources) as well as the Congolese IDAK (Investissement Durable au Katanga) for organizing the on-site visits and workshop. And it was even a trip down memory lane, as Fairphone first visited the southern province Katanga in 2011 when we existed only as an awareness-raising campaign. This second time around we had an actual phone to show off and a concrete objective – to find opportunities to source cobalt and to make our battery more fair.

Visiting various cobalt mines

Flying over the provincial capital Lubumbashi, we saw a great extended city of around four million inhabitants, more than four times Amsterdam, in the middle of a beautiful green lush landscape. Still, the area is a not so popular travel destination, as almost all other passengers left the plane one stop earlier, in Zambia.

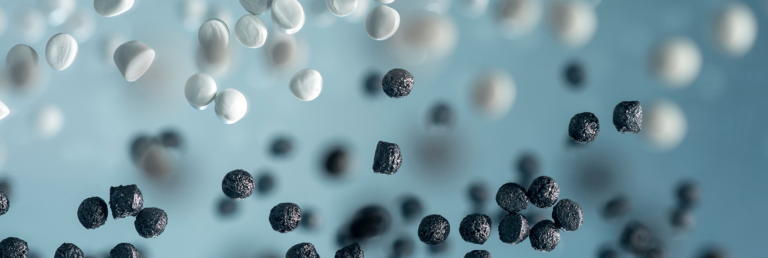

The Katanga province is known for its enormous reserves of copper and cobalt, more than 50% of the global mined cobalt production comes from the DRC (read more in our material scoping study). We visited various types of mines, ranging from purely manually operated artisanal sites – to more advanced industrial ones, also called large-scale mining. Compared to the eastern Kivu provinces (where we sourced tin and tantalum), Katanga has a much larger share of industrial mining, here only a small part of the production, about 15-20% is coming from the artisanal- and small scale mining (ASM) sites. This still encompasses an estimated number of 70,000 to more than 100,000 artisanal miners.

Differences between artisanal and industrial mining

On this trip, we saw striking differences between artisanal and industrial mines. Artisanal mining sites have little to no equipment used, no protective gear, and unsafe conditions such as tunnels that are not safely built. Further, these artisanal miners are mining often illegally on land designated for industrial mining organizations and therefore get into disputes with large-scale mining companies on the right to work in these areas. Artisanal miners do not work in the land designated for artisanal mining because they claim this land is not as rich in resources as the land for large-scale mining.

Further up the supply chain

Besides mine sites, we were able to observe additional stages in the supply chain for opportunities of improvement before cobalt leaves the DRC.

There are multiple marketplaces or depots, where traders buy directly from the mineworkers or from middle-men. We didn’t see a traceability scheme in place, so at this point it becomes difficult to say from which site the cobalt originates. The depots have tools to determine the quality of the ore, but offer little insight to the miners on how this grade and the prices paid are determined. The miners do not have much of a bargaining position and must take the price offered, which miners suspect to be far below the actual market prices. Here there could be better ways for miners to negotiate the value of the ore they mine.

Workshop with local and international stakeholders

Together with two German development organizations BGR and GIZ as well as the Congolese IDAK, we co-organized a two-day workshop in Lubumbashi. In this workshop, we discussed the practices and issues we had seen on our on-site visits and discuss with other stakeholders whether there were any shared opinions on possible solutions as well as existing programs already happening on the ground which could be linked to. About 40 local and international parties attended, including government authorities, mining cooperatives, individual miners and NGOs.

There are currently various initiatives starting on cobalt in the DRC and we wanted to take this opportunity to discuss them with relevant stakeholders on the ground. With the world demand for cobalt on the rise and many communities still highly dependent on a very problematic mining sector, it becomes more and more urgent that a transitional strategy is being developed and implemented.

Discussing ways forward

A real change requires all stakeholders to come together and to get a shared understanding of the most pressing issues and the existing challenges to address them. A number of improvements for the artisanal mining sector were proposed, such as addressing issues like legal rights to land for mining, traceability, improving health and safety and increasing income for miners and their communities.

We also identified opportunities, some of which are already happening like local concentrators (mentioned above) that are directing significant efforts to get a more transparent supply chain and are training local miners on the need for more responsible practices. Also there are already some great initiatives on-the-ground addressing child labor which could be expanded.

Now it’s your turn! Do you have questions for Laura? Join our Ask Me Anything on Tuesday, 13 June, beginning at 17:00 (CET) on our Forum.

Thanks again to the following partners for organizing the visits and workshop: GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH, or German Development Cooperation), BGR (Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources), the Congolese IDAK (Investissement Durable au Katanga).