Tin and Tantalum Road Trip

What happens when the minerals, tin and tantalum, leave their mines in DR Congo and make their way into the supply chain all across the world? And, how does it finally end up in a Fairphone? In this blog, I’d like to explain the journey these minerals make from the source to your phone. As touched upon in the last blog on the production timeline, you have noticed that we are doing lots of stuff here at the Fairphone office. And yes, it’s true we’re running around to actually produce this phone. But besides the practical arrangements involved in the assembly, testing, certifications and all that stuff, we are of course still also looking at the other end of the phones’ life cycle. So, time for a closer look at the minerals with which all of this began: conflict-free tin and tantalum from DR Congo, the building blocks of the first Fairphone.

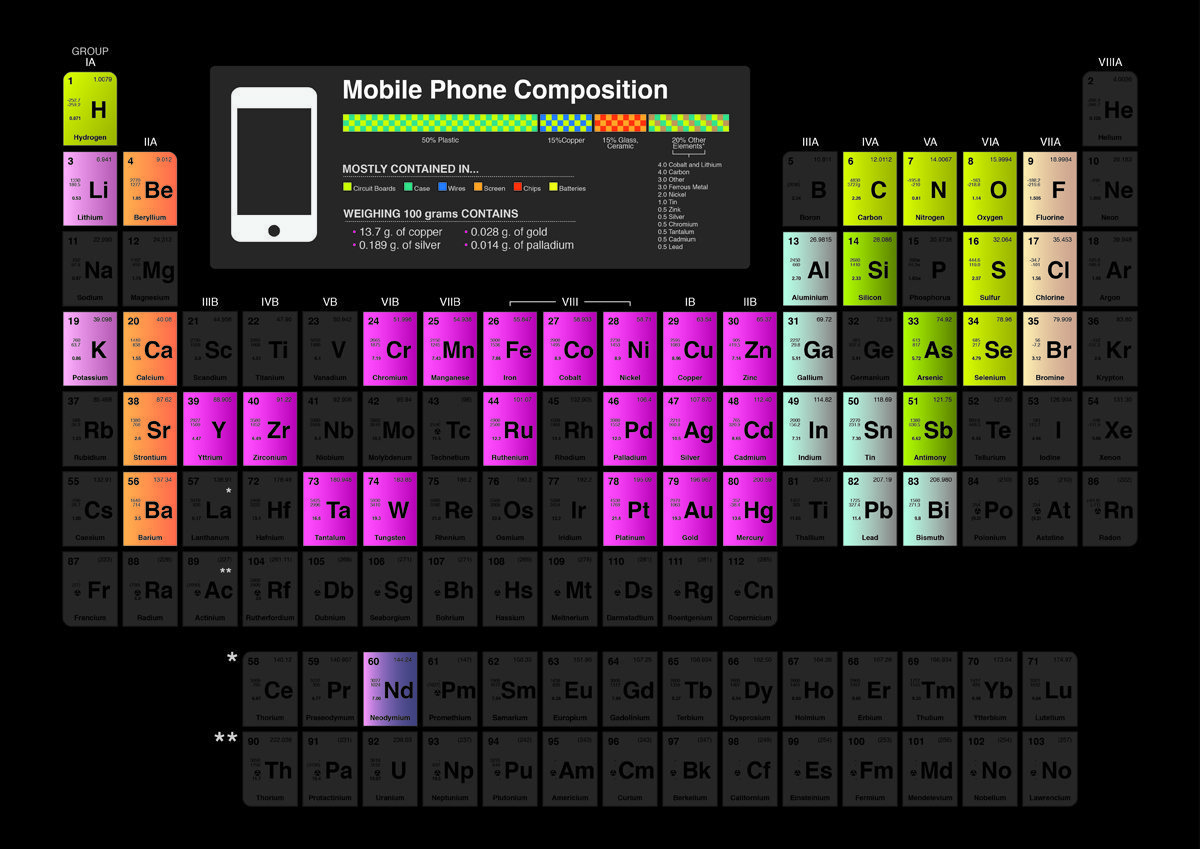

And indeed it has been a while since we discussed conflict minerals and the issues around the mining of these precious materials. In short, as you may already know, we are trying to make sure that minerals that end up in your phone are not funding war, thus these minerals are called “conflict-free minerals.” We have identified two so far, tin and tantalum, but this is a first step with a long way ahead, as there are 20 to 30 minerals in an average smartphone!

Source map: Visualizing the journey of tin and tantalum

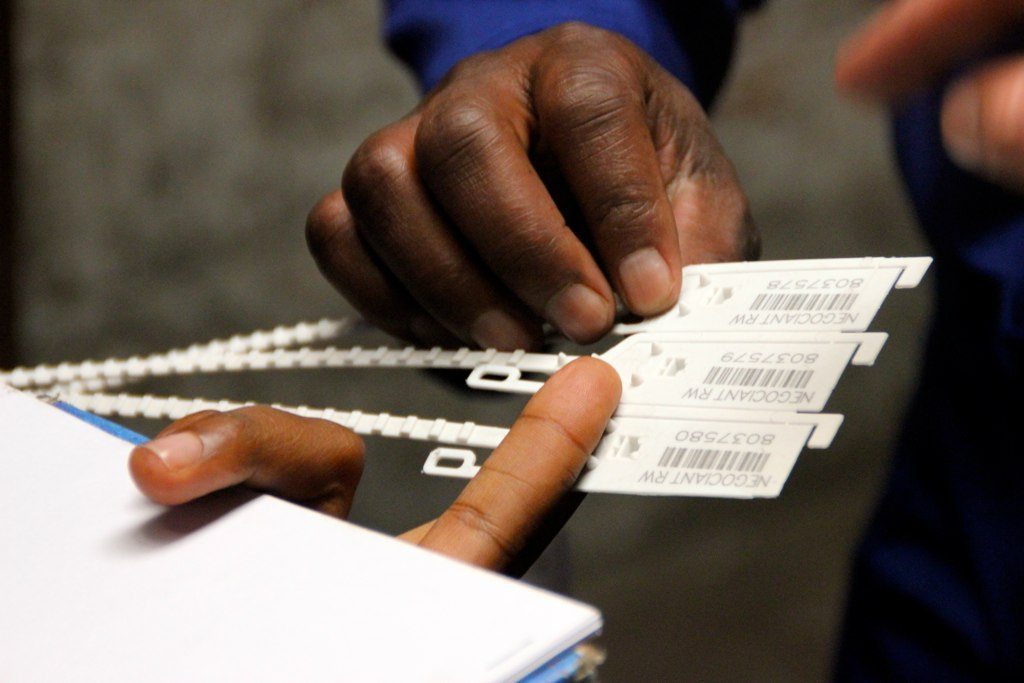

All right, that being said, back to the journey. If you prefer picture to text – skip ahead to the source map below! So, at this point of export the tin and tantalum are ready to begin their international travels. This is how they travel to get into your phones: the tantalum is first shipped to Kigoma, Tanzania where it is further transported by road to Dar es Salaam. Then it’s shipped to F&X in Guangdong, China, a CFS-compliant smelter that refines the raw ores into tantalite powder and wire. CFS-compliant means that the smelter is part of the conflict-free smelter program, a program in which the smelter is frequently audited to guarantee that it is not using any conflict-financing ores (also an interesting topic, possibly for next time!). If that’s all done, the refined material is shipped to the Czech Republic, where AVX makes our tiny friends, the capacitors.

The tin, on the other hand, has a completely different journey. The tin is first shipped from Bukavu (Congo) to Dar es Salaam. There it’s shipped to Malaysia to the smelter (also CFS compliant) to eventually be produced into soldering paste in Bangalore, India. Then both the capacitors and soldering wire are finally shipped to Hong Kong, to arrive at our factory in Chonqching, China.

I could keep writing on and on about where they go next, but I thought we should take a break and see a nice pictorial overview. So, check out this nice source map by clicking on it to see how the international travels of these minerals continue over land and sea. This source map will be updated along the way, as we gather more information on different layovers they might have on their way and updated info on processes and reports.

Facts about mining tin and tantalum

Allow me to take a small detour with some facts, just because I can’t resist the temptation: there are very few large tantalum mine sites around the world. The biggest industrial tantalum mine was found in Australia which is also where, after Brazil, the main world reserve of tantalum is reported to be. However, this one recently closed, as well as other large mines, for example, in Ethiopia. And why? Because the industrial exploitation of tantalum is often not too profitable. Tantalum is quite hard to extract with large machinery as whole blocks of stone need to be crushed to find small amounts of tantalum. Artisanal mining however, provides the flexibility to “follow the tantalum” and stop digging when and where the tantalum trail ends.

As artisanal mining is very common in East Africa (also because the deposits of minerals in the DRC are rich but not necessarily large and therefore do not require mechanical mining) sourcing from the Congo sometimes seems more lucrative, as it is more likely to source from there as big mines elsewhere in the world are closing. Keep in mind where the big reserves are located in the world: For tin, it is reported that even 40% of tin reserves are located in the DRC, while 40% of the world tin production originates from Indonesia. Another interesting detail I want to mention: one of the biggest users (consumers) of tin is the automobile and aviation industries. So you see, the electronics industry is not even the biggest user of tin!

At the factory

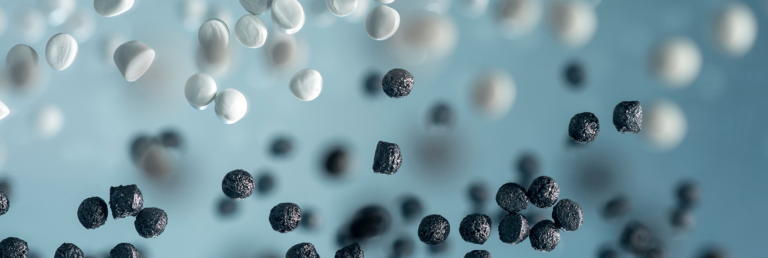

Back to our road trip! Your conflict-free tin and tantalum by this time has arrived at our production partner’s factory in Chongqing. Once the tin is inserted into the assembly process, what exactly ends up in your phone? Well, using just tin as an example, CFTI tin is blended with other conflict-free tin to produce the final product, that is, soldering paste, as the quality of tin fluctuates and the produce from Congo is not extremely high. Imagine immense kettles where tin from all over the world is blended together and distributed to different facilities around the globe to be used for different materials. Our soldering paste manufacturer Alpha was able to trace the CFTI tin all the way to your phone through a separate production line which is quite an unique achievement! (We could talk a lot more about this process, but again, this deserves a blog in itself.) We are producing 25,000 phones with this paste. To produce this many phones, we need around 25 kg of soldering paste – so do the math!

This short trip around the world has taken us from the mines of South Kivu and Katanga in DR Congo to China and Malaysia and the Czech Republic to India to finally arrive at our partners in Chongqing, China. I hope I’ve shown you the complex logistical and geographical hurdles needed to get conflict-free tin and tantalum from Congo into the Fairphone and what a challenge it is to trace these materials back to their source. In the future, we’ll definitely provide more details on as many stops on this journey as we can, and hopefully add more of its itinerary to this source map. So keep posted!